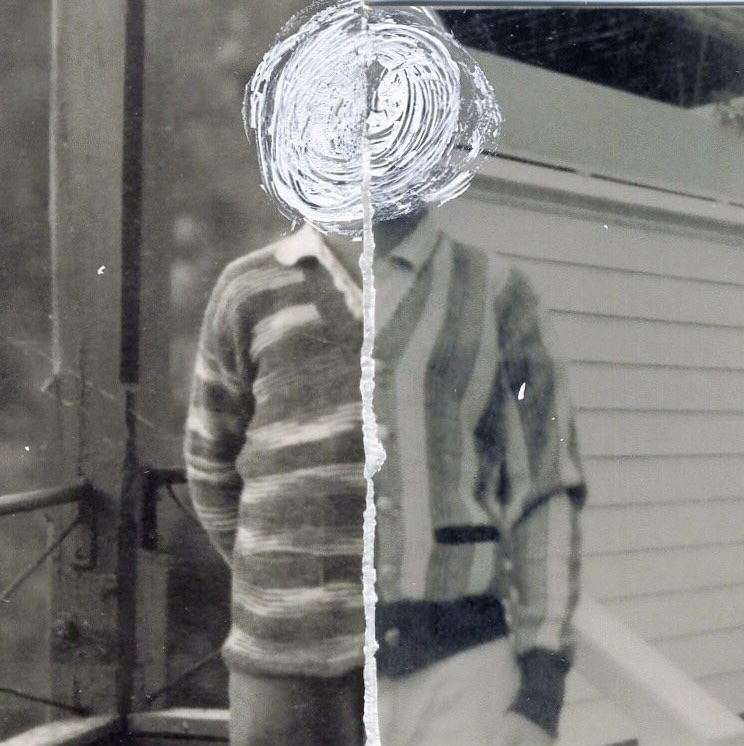

It is with sadness we communicate the passing of the cosmonaut boy after a long illness. Nobody knew why he wore the space helmet. It wasn’t a cheap plastic toy or old movie prop, but a thick globe two sizes too big for his head, the glass mottled and white like a soap-scummed fishbowl he’d stolen from the pet shop. Nobody knew what his face looked like. He kept the visor pulled down. He never took it off. Like he was waiting to be abducted by aliens. We said he’d been in an accident during a fallout drill in school. We said he was sick. We said he was touching himself in the girls’ bathroom at church and God cursed him. We said he was a Russian spy. A medical experiment gone wrong, we said. But nobody knew for sure. There was a small bullet hole on the helmet’s left side where his cheek would have been. Milky cracks radiated from the hole like spider webs. Nobody knew if he’d been shot or shot himself. Nobody remembered when he was born. It was like he’d always been part of the town. Our ghost. The canker in our mouths we licked, hoping it would go away but never did. All my life has been a head full of stars, he spoke with his fingers. Nobody believed it. Nobody knew his name. So, we called him Nobody.

It is with sadness we communicate the passing of our Baba who never married and only ever wore black. Her right arm was longer than the other. From too much hugging, she joked. The children hated her. They said she had zippers on her forehead. We laughed and said those were just varicose veins, just wrinkles. For a small fee, she’d show up at your house and pretend to be your Baba. A rent-a-grandmother. She baked cookies and played teatime She taught the children hide-and-go-seek. She sang lullabies and showed children her collection of Vaseline glass. She bought them at antique shops, garage sales, and flea markets all over the state. Plates, teacups, silverware, decanters, and candlesticks all laced with uranium. At night they glowed pale neon green. When she visited, she gave the children a piece of glass to keep by their bed. A nightbright, she called them. Slowly, the children’s hair turned white. Their skins bleached. The church elders tried to stop it from getting worse by calling down blessings from heaven and baptizing all the kids again, but nothing worked. It’s the nightbrights, our Baba said. Her spit was white as angel tears, and her teeth rattled like loose piano keys. More and more children had white hair and pale skins. The games of hide-and-go-seek lasted longer. Nobody could be found.

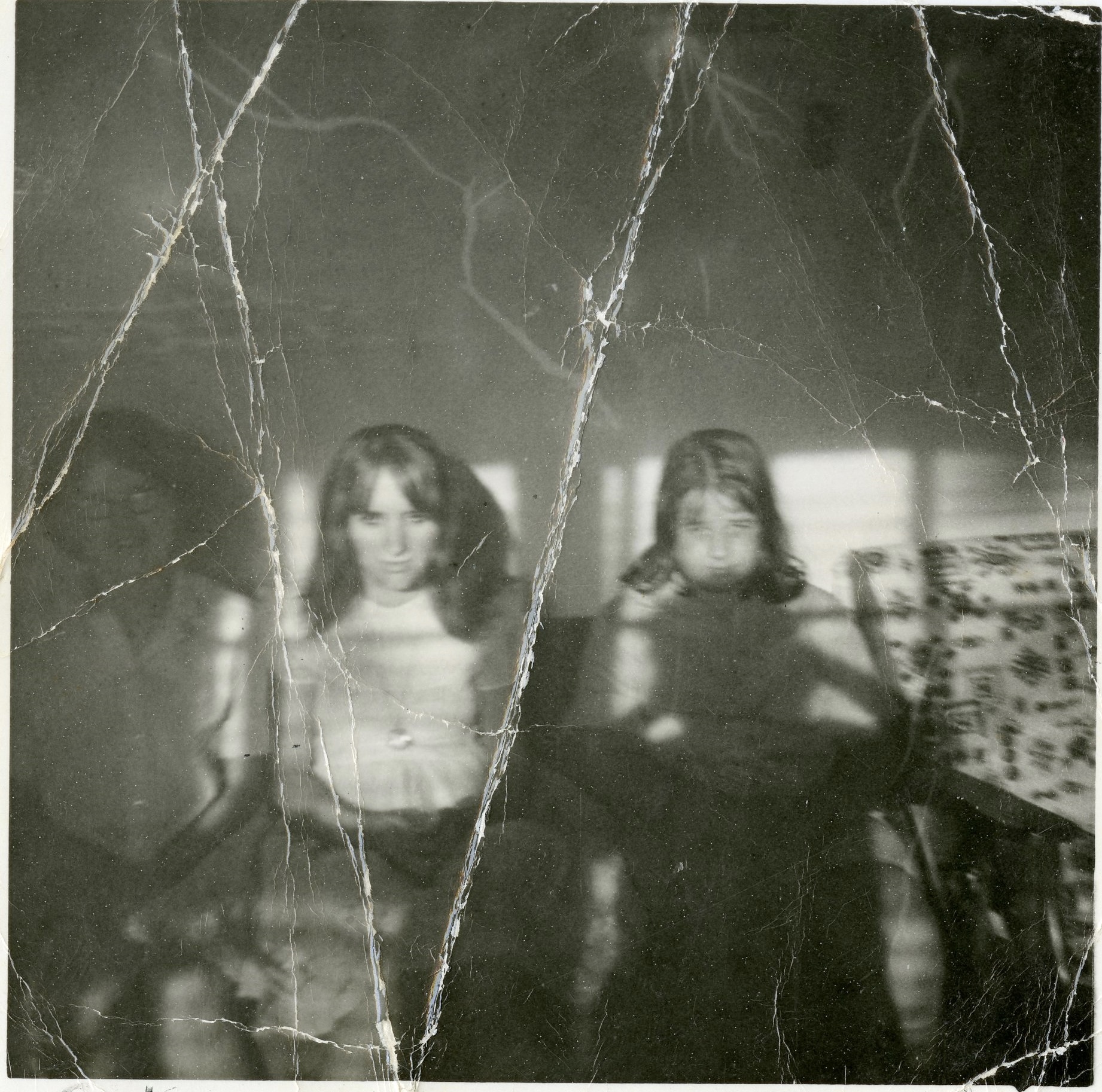

It is with sadness we communicate the passing of the movie theatre projectionist who perished during the wedding ceremony. She is survived by her sister. They met at a funeral when they were just young girls. While everyone else sang hymns, the girls took turns on the tire swing outside the chapel. Blood blisters, they clasped hands and promised each other. The only way to tell them apart, supposedly, was one of them liked to cut herself on the thighs, leaving behind long milky scars. She couldn’t help herself. It was a compulsion, she said, a kind of worship. Her fiancé liked to trace his finger over them as if they were a secret alphabet. The wedding took place yesterday inside the movie theatre lobby. Before signing her name on the certificate, the bride escaped through the back door and, successfully outrunning her fiancé, threw herself off the bridge. To prove, her blood blister later said, she was sane.

It is with sadness we communicate the passing of the housewife, a victim of the milk epidemic. It’s been all over the news. Beware of tuberculosis. And mad cow. And milkpox. Farmers everywhere blowing their brains out. The apocalypse is just around the corner, reporters say. The housewife stockpiled: 2%, skim, buttermilk, soy. She studied the cartons with faces of missing children. Doe-eyed, floppy hair, crooked smiles. She invented daydreaming. Aliens abducted them. Or perverts. Or polygamists. Everybody had a theory. It’s all a corporate scam, her husband told her, saying the companies got tax breaks if they advertised a public service. The pregnant housewife poured milk down the drain and clipped the missing children’s faces into a scrapbook. There’s a pattern here, she told her pregnant friends at church. Only children with some names get kidnapped, while others don’t. So there must be a safe name, a name that will prevent a child from ever going missing, she believed. She spent all day at the library trying to pick the right name. She drew pictures of what her not-yet child might look like and had extra sonogram printouts made, wondering if the fetal face belonged with the others on milk cartons. She developed strange cravings: wads of notebook paper and ink from broken pens sipped like wine. She walked into the canyon and ate handfuls of sandstone from the ochre cliffs. It stained her fingers red. Her doctor said it was a nervous disorder. Many women have it, he told her, giving her a vial of pills. Her husband got hooked on them. They kept him awake. That’s when they visited him—his babies in heaven waiting to be born. Three of them ready to lose their wings, he said, their bodies fuzzy and blurred, like they were out of focus, he said, but that’s how you know it’s an angel.

It is with sadness we communicate the passing of the stockyard worker who stumbled too close to the platform edge last night just as the train arrived and was smartly bisected by the incoming locomotive. Half the man fell onto the rails while the other half remained on the platform. It was a gruesome scene. His wife arrived in time to share a private moment with the bisected man on the rails who lovingly touched his wife’s lips and curled a finger in her hair. The other half muttered obscenities while the crowd watched. When asked if she wished to say anything to her husband’s other half, the woman refused, confessing her husband was a drunk and often violently beat her. This, she said, pulling her half-husband closer to her, is the man I’ve been waiting to fall back in love with all my life.