Nonfiction by William Lessard

Traditional grief literature starts its clock the moment the lungs of the decedent compress around their final breath. Not included in the countdown to denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance is the calculation that grief begins long before, when no one would think to log a time.

In the case of my mother, my grief started the moment I realized that the medical alert device was around her neck the entire thirty-six hours she was lying on the floor of the back bedroom.

Grief doesn’t attend to Fordist efficiency. Unless the death is unexpected, grief is a slow erasure.

In Basquiat (1996), Jean-Michel, played by Jeffrey Wright, is walking up Lafayette Street carrying a three-foot cartoon duck when he hears that Warhol has died.

Where we are the moment someone close is revealed to be a ghost.

Where we are when it becomes real that they have been a ghost all along.

Where we understand we are also ghosts.

I was 3,500 miles from the chair in which my mother was found “unresponsive.” When the doctor called with the news, I was standing at a tradeshow booth, where a vendor was demonstrating software that enables you to mirror your facial expression in 3-D.

Jessica Mitford wrote The American Way of Death (1963) to expose the upselling tactics of the American funeral industry.

I had a paperback copy I used to thumb through on nights my insomnia approached the four o’clock hour. As she ranted about “grief counselors” and other amenities, Mitford always struck me less as a defender of the sanctity of the death ritual and more as a person who fought with the power company every month over a $0.25 service charge she didn’t recognize.

Mitford died in 1996. Her passing was the dry toast and black coffee of funerals: cremated without ceremony, her ashes scattered at sea. Her funeral cost $533.31, including $475 for the cremation and, I would guess, the rest for gas and the bologna sandwiches given to each of the mourners.

My mother’s funeral cost ten times what Mitford paid. She lived eighty-eight years—thirty of them as a case worker assistant for Adult Services. She retired at sixty-five, with a small pension from Westchester County. She had never been on an airplane and would never think to go anywhere outside the neighborhood. When the time came, she wanted a funeral like any other, marking a life she believed was unremarkable and forgettable. It was what life was to her: something gotten through with the least amount of show.

Long ago, a lover of mine bought a religious medal in a shop near Plaza del Sol. The medal was oval, with the Virgin Mary peering out, in gold silhouette.

She was older. Married. The medal was a gift for my mother, she claimed, for “making such a beautiful son.”

The medal dangled from my mother’s neck for the rest of her life. I had forgotten about it until my wife handed me that brown envelope. Inside was the medal, along with the emerald ring my mother had fitted over the mark left by her wedding band.

Among Catholics, it is believed that the Miraculous Medal, as sacramental, “disposes us to receive grace.”

My lover’s mother had died a few months before. That afternoon was the last time we saw each other. Tonight, I realize the medal was never for my mother. It was always for me, for that morning twenty-eight years later.

Mourning is grief that uses the entire box of Kleenex. Grief is mourning that thinks the Kleenex is for blocking the sound of its own voice.

After the funeral, when the transaction was complete, the dark clothes put away, I was expected to assume normal dress, normal functioning.

All grief has become disenfranchised grief, a grief that is not socially acceptable, like mourning the loss of a friend to suicide.

The exception is social media mourning. Mourning online de-reifies the experience, makes grief part of twenty-first century capitalism. Because the “feed” offers an algorithmic revenue stream, tagged to everything we type, grief is once again permitted.

My mother, my feelings about my mother. Nothing exists unless it can be monetized.

Among Hindus, death resides with inherited impurity. The immediate family is not allowed to perform any religious rituals, nor can they attend parties or other social functions. The family in mourning is required to bathe twice a day, eat a single simple vegetarian meal, and confront their loss with the private diligence of the contagious.

The other night I was watching a horror movie. A mother conjures up her dead daughter instead of facing the pain of mourning her. For her refusal, she is possessed by a demon that forces her to saw off her own head while hovering six feet above the floor.

Grief is a fissure, the pinhole through which History enters.

I grew up feeling that the life I was given was an illness I wasn’t allowed to talk about. Every time I got a girlfriend, my mother always reminded me “not to tell anyone too much.” I grew up behind nicotine-stained lace curtains my mother thought no one could see through.

Have you ever visited a friend’s house with a fist-shaped hole in the living room wall?

Have you ever wondered why your friend is living at his grandmother’s while his parents are five blocks away?

Did it ever seem strange that your friend’s father was waiting to take the bus to work, even though his car was parked in the yard?

What did you think when your friend ran out the back door of school when he saw that emerald-green 1972 Malibu right in front?

Grief at sixty days: I can taste the puréed hamburger she refused, ten minutes before asking to be wheeled to her usual spot in front of the TV.

Grief at thirty days: life underwater; in my pocket, a kiss.

Grief now: the bill for my mother’s uneaten hamburger is tucked into a red folder too thick to close.

Each time he slaps me, I can smell the nicotine on the back of his hand. People on their way to work slow down to watch.

I’m not sure where my mother is. Maybe still inside my grandmother’s apartment. Five minutes ago, she told me to come out here. She said my father was “sorry about everything and wanted to talk.”

I’m wearing my school uniform. Gray plaid jacket, navy tie. The tie is wound around his left fist. I can feel the sides of my face going from stinging to numb. Someone across the street yells at him to stop. He gives me three more quick slaps, loosens his grip at my chin. I drop several inches, back onto Furman Avenue.

To be beaten is to have the self ripped back from the bloody seed from which it grew.

To be beaten is to know that the bloody seed is often all we have.

When you are a kid, it is assumed you don’t understand.

When you are an adult, it is assumed you don’t remember.

Her marital status is the only reference to her assailant. Her life unfolding beneath a raised seal. Under cause of death, an immediate cause, or what the physician’s handbook calls “a clear and distinct etiological sequence.” No reference to the scar on her left bicep. Also missing, my testimony: I was there when it became her and she became it. Saw the mug of coffee emptied mid-air across a kitchen table. The pink eruption of flesh dabbed with pinched cotton for the next six months. And in the remaining decades, the skin cooling into a milky thickness six inches long. Nothing to suggest the slow-moving death it became. My mother was murdered—just not right away.

Note:

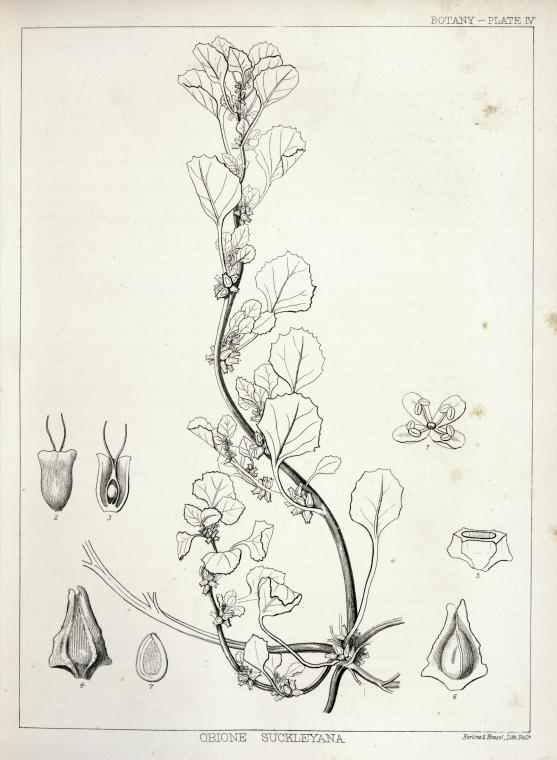

Seed image from General Research Division, the New York Public Library. “Obione suckleyana, 1. Staminate flower spread open, 2. Pistillate flower in its involucre, 3. Same vertically divided, 4. Fruit in its involucre, 5. Cross section of the same, 6. Longitudinal section of the same, 7. The seed vertically divided. Details variously magnified.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1860. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-5671-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99